As one of the only women to ever gain acceptance into the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, Vigée-Lebrun submitted “Peace Bring Back Abundance” in her application. As a portrait artist, an allegorical painting such as this was unusual for Lebrun. During the French Enlightenment, some genres of art, such as historical and allegorical paintings, were considered superior to other, such as still life and portraiture. Considering Lebrun’s profession in portraiture, and the fact that the large majority of applicants accepted into the Royal Academy were men, this compromise on Lebrun’s part is suitable. Additionally, Lebrun’s ties with the royal family, as Marie Antoinette’s favorite portrait artist, diminished Lebrun’s chances of acceptance even further, as the Academy wanted to remain an institution separated from the influences of the crown. In fact, Lebrun’s admittance would have been impossible without the interference of King Louis XVI.

There are many revolutionary qualities of “Peace Bring Back Abundance,” displaying the personified themes of peace and abundance during a time period riddled with poverty, famine, and uprise. Created in 1780, Lebrun portrayed this piece directly after the American Revolution and before the French Revolution. In fact, the use of allegory itself was revolutionary was this genre was largely associated with carrying “emblems of revolutionary power” through portrayal of the “incarnation of revolutionary values” (De Baecque, 111). The timing for this painting almost certainly suggests an incentive to create a political statement on behalf of Lebrun. If anything, it conveys the importance of foods such as wheat and fruits, to those who rebelled against their sovereigns. The French Revolution is largely remembered for events such as the Women’s March on Versailles, a demonstration held to call attention to the high prices and scarcity of bread. In fact, Marie Antoinette, a woman closely associated with Lebrun herself, is remembered for having allegedly said “Let them eat cake” in response to the bread riots spurring all over France. This painting, at the very least, indicates the idea that food supply and peace go hand in hand.

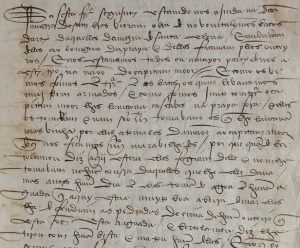

Vigée-Lebrun could also have been making a statement about gender roles during Enlightenment France. The painting depicts Peace, a woman draped in dark colors, holding an olive branch and gently leading forward Abundance, also embodied as a woman. Abundance contrasts Peace by wearing white clothing, exposing her breast, and holding wheat and grains as well as various fruits. Due to the contrast in colors, Peace can be interpreted as a male figure and Abundance as a female considering the “darker flesh tones and hair color traditionally used to indicate maleness, the pearly flesh and blonde hair to suggest femaleness” (Sheriff, 126). This indicates a broader theme about gender roles, as Abundance is sexualized through her lack of clothing, as well as her suggested virtue through innocence in her light color schemes and dependence on a male figure. Here, Lebrun’s attempts to insert feminist themes into a painting that would harbor a largely male audience.

Sources:

Image Vigee-Lebrun, Elisabeth Louise. “Peace Bring Back Abundance.” Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/638218.

De Baecque, Antoine “The Allegorical Image of France, 1750-1800: A Political Crisis of Representation” Representations, Vol. 47 (1994):111-43.

Sheriff, Mary D. 1996. The Exceptional Woman: Elisabeth Lebrun and the Cultural Politics of Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.