Silk and Metallic thread

The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of Florance Waterbury, 1943 ; 43.144

One of the underlying reasons for European expansion into the Americas was the pursuit of a westward passage to Asia. China, particularly, held a place of wonder in the minds of Europeans who began to imitate its signature goods in what became termed “Chinoiserie.” Although for Europeans, the East was a trading partner providing goods such as spices, tea, and ceramic china, some of the goods that flowed out from the east were harder to come by and therefore less a commodity to be traded than an artifact or a curio that, inevitably, inspired European imitation.

One such item that inspired Chinoiserie were the silk robes worn by courtiers in the Ming dynasty court. In their original context they were a symbol that communicated a social status. The Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci, had to repeatedly petition his superior, Father Valignano, head of the Jesuit mission in Asia, for the ability to wear such robes so as to gain access to the imperial Chinese court. The robe he wore was likely similar to the one pictured. Ricci picked the robes of a Daoist to communicate his role as a priest, albeit of an entirely different faith.

Although the French sericulture industry was created by Chinese silk work that had made it to Europe prior to the late 16th century, it was the Jesuit missions of 1582 that began shipping Ming Court robes to Europe that reinforced the French practice of imitating Chinese cloth. British travel writer, John Evelyn, came across Ming robes shipped by Jesuits as they stopped over in London on their way to Paris. In his diary from 1641-1697, he described robes having “splendor and vividness we have nothing in Europe that approaches it.”

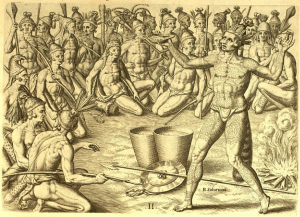

The french imitation cloth came to be known as ‘Damas de la Chine’ and was frequently worn among French nobles to demonstrate wealth and status. An important moment frequently used by historians to demonstrate the importance of China on the Global stage in the early to mid 17th century is that of Jean Nicollet. He was supposed to have met with the native tribes of Wisconsin wielding pistols and wearing a Chinese robe. Historians recount this story to suggest that Nicollet likely thought he was to have set foot in China and was dressed to appear in Ming court.

This story likely arose due to a series of mistranslations. What Nicollet probably wore was not a ‘robe’ but a cape of ‘Damas de la Chine.’ This fit his ambassadorial role as the first French ambassador to make contact with this tribe. Nicollet was dressed in the formal attire of a French gentleman of his time.

Ming robes still serve to demonstrate the currency that China had in European minds. Nicollet wore a cape made out of a French imitation of a Chinese cloth as he was in a pursuit of a westward passage to China achievable by ship. In a sense he doubly demonstrated the importance of China to Europeans. Chinese exports like the Ming robes inspired European industry in chinoiserie as well as fueling the European desire to push westward through the new world.

Sources:

Brook, Timothy. “Vermeer’s Hat.” In Vermeer’s Hat, 49–51. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2008.

Jacobson, D. Chinoiserie. Phaidon Press, 1999. https://books.google.com/books?id=Km7FQgAACAAJ.