Oil on panel

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

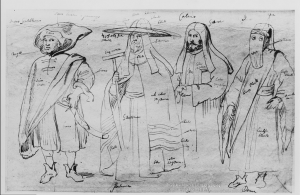

Coffeehouses are intimately intertwined with the spirit of the Enlightenment. Coffeehouses like the one depicted here by Joseph Highmore were places of intellectual debate and helped facilitate the transmission of new ideas and modes of thought. The central figure in this painting is clearly in the midst of an impassioned debate. He and his peers wear dignified clothing while the boy on the right seems to be serving them coffee.

Although the Enlightenment was a time of revolutionary thinking and new ideas concerning the inherent dignity of all human beings, not all groups of people in Enlightenment-era Europe enjoyed immediate or lasting benefits as a result of these new modes of thought. European Jews constitute an example of one such group, and their plight can be analyzed through the lens of the quintessential Enlightenment institution: the coffeehouse.

Yes, even in these dens of high-minded discourse long-standing biases against Jews prevented them from enjoying the full effect of Enlightenment thinking. There are numerous reports of Jews being barred from entering Christian coffeehouses. This also extended to the coffee trade with the denial of Jewish access to trade markets. Jews were promised increased economic freedoms in this era, but these freedoms oft went unactualized.

This period is understood to be a time of increased religious freedoms, but it is fair to ask the question: were the lead figures of the Enlightenment genuine in their support for tolerance? Voltaire might be the most prominent figure of them all, but one need not look far to see that he was no fan of the Jewish people. He frequently spoke of his disdain for the Jews, yet he was a staunch supporter of religious freedoms. Voltaire was far from the only Enlightenment figure to hold these seemingly contrary views. Thus, this constitutes the central paradox of the Enlightenment. Yes, the thinkers of the Age of Reason have greatly influenced political institutions and our modern conception of morality, but many of them held views about minority groups, particularly the Jews, that today we find repulsive.

Coffeehouses provided a certain few with the ability to discuss lofty ideas, but it is important to consider who is left out when viewing an Enlightenment-era painting such as this one. At the far left of the painting, one coffeehouse patron is grabbing the neck of a visibly distressed woman while the others pay no mind and continue on with their discussion. Here Highmore unwittingly encapsulated the failures of the Enlightenment. In this era, rich white men discussed and wrote about important and worthwhile topics, but marginalized groups did not stand to benefit nearly as much as those rich white men. In many cases, as is the case with this painting, the men were the very ones who were subordinating these groups.

Sources:

“Figures in a Tavern or Coffee House – Joseph Highmore – Google Arts & Culture.” Google Cultural Institute. Accessed December 10, 2018. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/figures-in-a-tavern-or-coffee-house/JQG0Ko6r2Seg6w.

Lausten, Martin Schwarz. “TOLERANCE AND ENLIGHTENMENT IN DENMARK: The Theologian Christian Bastholm (1740-1819) and His Attitude Toward Judaism.” Nordisk Judaistik 19, no. 1–2 (1998): 123–39.

Levy, Richard S., and Albert S. Lindemann. Antisemitism : A History. New York, NY: OUP Oxford, 2010. https://login.avoserv2.library.fordham.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=694173&site=eds-live.

Liberles, Robert. Jews Welcome Coffee : Tradition and Innovation in Early Modern Germany. The Tauber Institute Series for the Study of European Jewry. Waltham, Mass: Brandeis, 2012. https://login.avoserv2.library.fordham.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=447952&site=eds-live.

Voltaire, and Simon Harvey. Treatise on Tolerance. Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy. Cambridge ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 2000., 2000.