Fray Diego Durán, 1570’s.

Early nineteenth-century facsimile.

Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

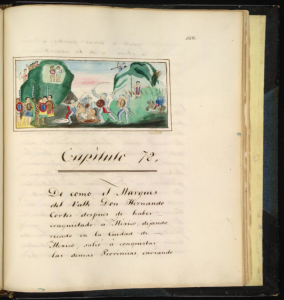

Durán, Diego. “De como el Marquis del Valle Don Hernando Cortes. . . salio a conquistar las demas Provincias . . .” [Cortés and Soldiers Confront the Indians]. In La Historia antigua de la Nueva España. 19th Century. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. Facsimile. November 2018. Library of Congress.

Horses have become an iconic characteristic of the Plain Indians of North America. There is an assumption that these people were always mobile through their access to horses. In reality, these long-sedentary societies were disturbed by Spain’s introduction of horses. This mobile beast gives the Plains Indians their iconic tradition of being nomadic. The introduction of horses caused different native nations to come into conflict, not only with each other but with the labor force on Spain’s territories. In reaction to the intersection of various races, the colonial government created a system to label backgrounds. The racial hierarchy that the Spanish developed was an attempt to reassert their dominance after their inability to maintain their monopoly on horses that they initially enjoyed over the Indians.

A painting from Fray Diego’s manuscript depicts the symbolism of the horses that the Spanish brought into colonial territories. This manuscript was made in the 1570’s and was not published until the 19th century. In Fray Diego Duran’s manuscript, he recorded his observations of the Indian’s society. In one of his sections, he includes a colored depiction of the confrontation between the Mexica and the powerful Spanish forces of Hernando Cortés (1485–1547) during his campaign of 1519–1521. Understanding that Fray Diego Duran was a Spanish Dominican priest, it follows that he would depict the Spanish as the superior people in the confrontation. The “history of the Indians” manuscript was likely tailored for the nobles and learned men in Spain who were not able to experience first-hand the New World. The history could also be for the patrons that financially backed the trip. In the piece, horses are leading the Spanish in the fight against the Indians. For the Spanish, this symbolizes that they are justified in invading the Indian’s land. In. Spain, horses were notable elements of heroic traditions. They represented the honor and valor of the rider and thus a sign of nobility. This sign of nobility translated into New Spain, and thus the natives that began riding horses gained status. With the Spanish losing their sign of nobility, they had to turn to a racial hierarchy to reassert their dominance. The introduction of horses was the impetus for the Spanish to create the infamous racial hierarchy. Furthermore through horses we see that once technological advancements are distributed among different people, the divide among them are minimized.

Sources:

Earle, Rebecca. The Body of the Conquistador. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Mann, Charles. 1493. New York: Vintage Books, 2011.

Fray Diego Durán, La Historia antigua de la Nueva España, 19th Century facsimile, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, November, 2018, Library of Congress.

![[n.d.]. Citron x sour orange, Citrus medica L. x Citrus aurantium L.: whole and half-fruits. https://library.artstor.org/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003813548.](/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/41822003813548-300x233.jpg)