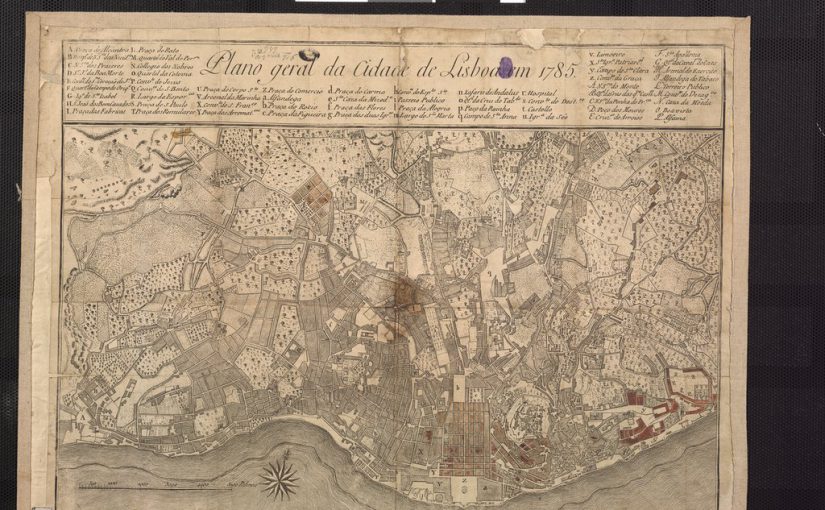

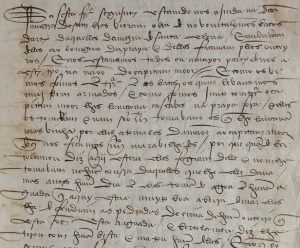

Line-cut Facsimile of Deutsche Messe

Martin Luther, Wittenburg, Germany. 1526.

Woodcut print book.

Luther, Martin and Michael Lotter. Deutsche Messe vnd ordnung Gottis diensts. Wittenburg: 1526.

“Martin Luther – Deutsche Messe 1526.” Martin Luther (1482-1546). Cedarville University Digital Commons. Accessed December 6, 2018. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/sing_martin_luther/1/.

This book is a facsimile of Deutsche Messe, a mass written by Martin Luther in 1526. Though the Reformation brought about the purging of art from worship, Martin Luther was a proponent of just the opposite: he believed that the art of music furthered the act of devotion. Luther specifically believed in the concept of musical ethos, which claimed that music had an ethical effect on the mind and body. According to his theory, good music, which led people to God with its emotional response, ignited the passion necessary to worship God. In composing the music of his Deutsche Messe, Luther hoped he would lead people to God and his theological doctrine of sola scriptura, sola fides, and sola gratia.

What sets Luther’s mass apart from other traditional masses is its use of German. By using the vernacular language, Luther believed that he could better communicate his theological principles to a German audience. Luther supported the theory that German people best understood God’s word in German hymns. In the Deutsche Messe, he matched the natural versification of the German text to explicitly German melodies. In doing so, Luther believed that his hymns made God’s word more intelligible to a German audience.

It is true that Luther did retain some elements of the traditional mass, namely the standard Latin hymns. Luther wanted the German people to be well-versed in Latin among other languages. He advocated for the German population to learn and understand Scripture in as many languages as possible, believing that it would allow them to spread the word of God to people wherever they went.

The Latin hymns which Luther chose to retain were strategically chosen so as to not reduce the intelligibility of the mass for the general German public. These hymns drew on well-known Catholic plainchants. Because the Latin text and melodies of these hymns had been standard in the traditional masses, most of the German people who engaged with Luther’s mass were already familiar with the Latin portions.

It is also important to note the increased accessibility of the Deutsche Messe in comparison to traditional Latin masses. The mass was spread widely among the young German population because it was incorporated into German schooling; students and teachers alike attended the mass and were familiarized with both the German and Latin hymns. The printing of the book, as demonstrated by the facsimile, also played a part in its accessibility. After the birth of the printing press, literacy rates in Germany increased dramatically. As a result, the book was easily accessible to the majority of the German population.

Another aspect of the mass which Luther found marketable was its novelty. Being that no prior mass had been written in the vernacular language, Luther hoped that the originality of the Deutsche Messe would attract non-Lutherans to his music and his theology. Whether or not Luther was successful in this pursuit is debatable. What Luther did accomplish, though, was the creation of a new type of mass which used vernacular language and music of the people to appeal to a specific audience.

Works Cited:

Anderson, Matthew R. “The Three Reformation solas and twenty-first century ethical issues.” Consensus 30 (2005). https://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus/vol30/iss1/5.

Cameron, Euan, ed. “The Power of the Word: Renaissance and Reformation.” in Early Modern Europe: An Oxford History, 63-101. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Foroughi, Louisa. “Spiritual Reformation.” HPRH 2003, Fordham University, Bronx, September 14, 2018.

Grew, Eva Mary. “Martin Luther and Music.” Music & Letters 19, no. 1 (1938): 67-78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/727986.

Lippman, Edward A. “The Sources and Development of the Ethical View of Music in Ancient Greece.” The Musical Quarterly 49, no. 2 (1963): 188-209. http://www.jstor.org/stable/740645.

Janz, Denis R., ed. A Reformation Reader. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Luther, Martin. Documents Illustrative of the Continental Reformation: The German Mass and Order of Divine Service, edited by B.J. Kidd. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1911.

Sternfeld, Frederick W. “Music in the Schools of the Reformation.” Musica Disciplina 2, no. 1/2 (1948): 99-122. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20531762.